As part of its efforts to remain competitive in the race toward ever more powerful AI capabilities, there is increasing recognition that Europe should invest in public AI. That is, AI systems built by organizations acting in the public interest and focused on creating public value rather than extracting as much value as possible from the information commons.

There is a wide variation of proposals floating around; we see an increased mobilization of public investments into efforts to build European AI models. Many of these efforts are mired in uncertainty about copyright. This is counterproductive and unnecessary since the EU copyright framework contains specific rules that allow public-interest organizations— such as research organizations and cultural heritage institutions—to train and make available AI models using all lawfully accessible works. These organizations are not required to obtain permission from copyright holders or comply with opt-outs..

Unfortunately, much of this legal clarity is lost in the fog of war surrounding commercial AI training and never-ending discussions about the applicability of the TDM exception to the training of AI models.

By giving both scientific research organizations and cultural heritage institutions a privileged position, the 2019 Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive uniquely positions these types of entities as developers of public-value-driven AI models. This aligns with the fact that many of the efforts to build publicly funded AI models in the EU are undertaken by either research organizations (such as GPT-NL in the Netherlands) or libraries (such as in Norway), often with the objective to make the resulting models available under open-source licences, allowing anyone to use and build upon them.

Article 3 of the CDSM Directive enables these institutions to text and data-mine all “works or other subject matter to which they have lawful access” for scientific research purposes. Text and data mining is understood to cover “any automated analytical technique aimed at analysing text and data in digital form in order to generate information, which includes but is not limited to patterns, trends and correlations,” which clearly covers the development of AI models (see examples here or, more recently, here).

Article 3 is an enabling legal framework for EU Public AI development

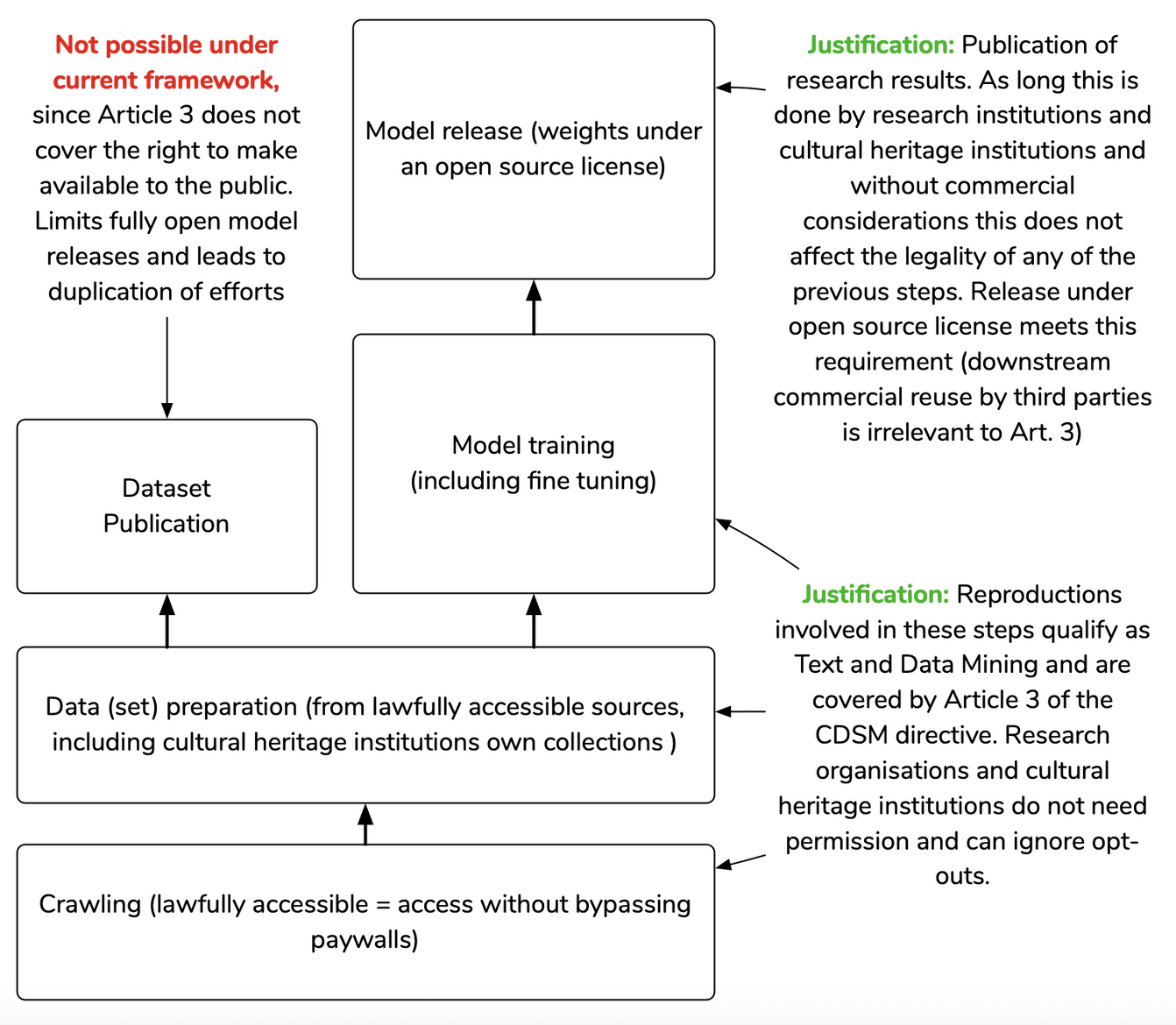

The figure below shows a more detailed analysis of how Article 3 applies to qualifying beneficiaries—including scientific research organizations and national libraries—that engage in research efforts to build large pre-trained AI models intended for release under open-source licences. The analysis pertains to training data that is protected by copyright.

The figure also shows that the three key stages of model training (data acquisition, data preparation, and the actual training) all fall within the definition of TDM (and, crucially, only involve reproductions and extractions). It also shows that the publication of training datasets containing copyrighted works does require authorization from rightsholders (because it involves the making-available right). Although training-dataset transparency is an important part of building fully open AI models, it is a separate process from training the model.

This mapping of the scope of the TDM exception onto the individual steps of the AI model-development pipeline is largely uncontroversial and shared by observers who dispute the overall application of TDM to AI training (see here) and those who consider AI training fully in scope (see here).

Releasing the trained model (i.e., the research artefact resulting from the text and data mining activities carried out in the previous steps) does not fall within the scope of the TDM exception. However, as long as the trained model does not contain any of the works that it has been trained on, making it available does not infringe any rights in copyrighted works that have been included in the training data.

In other words, when research organizations or cultural heritage institutions make their models available in line with their public-interest missions—such as by releasing model weights under an open-source licence—and refrain from commercial exploitation, the lawful status of reproductions and extractions made during training remains unaffected. In this way, Article 3 provides a clear legal basis for the entire model-development process pursued by non-commercial Public AI initiatives, from data acquisition to open-source publication.

This conclusion is also supported by a recent legal opinion authored by Prof. Dr. Malte Stieper for the German Library Association, which confirms that—under the German implementation of Article 3 CDSM—libraries “may produce text corpora with works from their collections to conduct TDM activities themselves, e.g., to train an LLM for analyzing the library collection” (author’s translation). The opinion further emphasizes that this applies only to non-commercial research contexts and that contractual clauses excluding such uses are not enforceable.

While Stieper’s analysis focuses on the role of libraries, it should apply mutatis mutandis to the other beneficiaries of Article 3 included in the above analysis. Importantly, he also notes that the law allows libraries to partner with research institutions as a “verlängerter Arm” (extension of the research organization) for concrete projects—further supporting the Public AI collaboration model.

Matching ambition with legal clarity

Still, many of those involved in attempts to build Public AI models complain about legal uncertainty and report pressure from rightholders aimed at preventing them from exercising their rights under the Article 3 exception. In an open letter to the Commission, leading European AI researchers involved in publicly funded efforts to build large AI models, they warn:

Unfortunately, uncertainty over how existing copyright law applies to model training is slowing European progress, and risks a future in which Europe invests heavily in infrastructure while others define the foundations of AI.

This uncertainty leads to inaction, preventing Europe from realizing its ambitions as expressed in the Apply AI Strategy and the AI Continent Action Plan. Both strategies share a clear aim: to build a competitive, sovereign, and trustworthy European AI ecosystem. The Union is investing heavily in this goal—from research funding and talent programs to large-scale infrastructure such as AI Gigafactories and AI Factories. At the same time, copyright questions are treated as if they were outside this ambition. What is needed instead is recognition that the space created by Article 3 is an essential enabler of public-interest AI development. The signatories of the open letter stress that:

Legal clarity on AI model training is as essential as compute power or funding — it is the foundation that enables Europe’s researchers and innovators to turn this strategic investment into open, competitive, and trustworthy AI models “Made in Europe”. Unfortunately, uncertainty over how existing copyright law applies to model training is slowing European progress.

To make good on its strategic ambitions in AI, Europe must leverage Article 3 by providing clarity on its scope of application for the very institutions on which it relies to deliver. Leaving them in uncertainty serves no one except competitors that can operate outside the European legal framework.Offering such clarity would not require new rules but rather a reaffirmation of the existing ones. An interpretative communication confirming that Article 3 covers model training by public research and cultural institutions on lawfully accessible data would send a clear signal that the EU’s AI strategy not only regulates AI but enables it.

To be clear, this should not be read as an attempt to remove creators, rightholders, and other information producers from the equation. Empowering EU researchers and public institutions to research and build frontier AI must not come at their detriment. But as we have argued elsewhere, tying remuneration to research and development of AI models is a dead end. To balance the strategic need to build a competitive public AI ecosystem with the democratic imperative to sustain Europe’s public information ecosystem, Europe should focus on redistributing value where it is created: at the point of deployment. One option is a levy or tax on commercial AI services offered on the EU market that were trained on publicly available information. The proceeds should flow back to creators and rightholders, and to the public institutions that maintain the public information ecosystem.