Over the past months, the issue of how to strengthen Europe’s digital infrastructure has risen to some prominence within the broader discussion about the future and competitiveness of Europe. Investments into Europe’s digital infrastructure feature in the European Commission’s white paper on Europe’s digital infrastructure needs (February 2024), they have been discussed by Mario Draghi in his report about The Future of European Competitiveness (September 20024) and they have been central to a newly emerging discourse about digital independence and a proposal for a Eurostack (September 2024).

These discussions and interventions are part of a broader emerging discourse on Digital Public Infrastructure (UNDP) and European technological sovereignty. Open Future has contributed to these discussions by arguing that in order to have real Digital Public Spaces that can serve as guarantors of many digital rights (Open Future, 2023), it is necessary to invest in Public Digital Infrastructures (Open Future, 2023).

All these discussions are taking place with a view to the European Union’s next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, has already signaled her intention to create new financial instruments to support the EU’s competitiveness, and to revise current funding programmes. The goal of these changes is for these funding mechanisms to serve an industrial strategy that better aligns investment with Member States’ policy objectives.

With so many different concepts and proposals in play, it seems appropriate to take a step back and provide an overview of the current debates, and how they relate to the different levels or layers of (public) digital infrastructure.

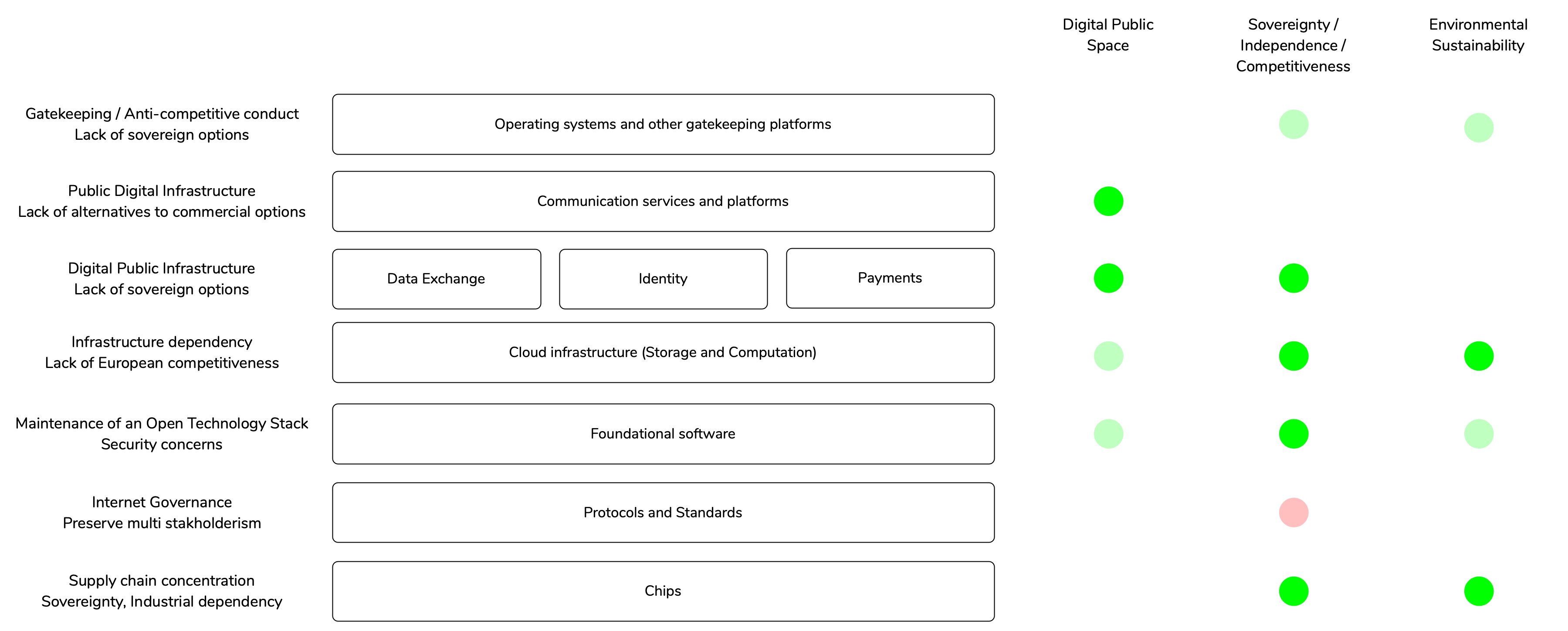

To do this, we start with the elements of public digital infrastructure that we identified in our Digital Public Space primer: communication services and platforms, storage services, identity services, underlying software functionality, protocols and standards. This initial list is expanded by considering a number of additional elements that are prominent in the current discussions: (cloud, clients, chips, data exchanges and payments. The diagram below presents these different elements as constituting a number of layers (on the right of the diagram). These are linked to various discourses and proposals that make up the discursive space (on the left of the diagram).

The metaphor of the stack originally refers to the interconnected layers of technology that make up the global digital infrastructure (Bratton, 2016), including hardware, software, protocols and data. Unlike traditional hierarchical models of infrastructure, the stack is dynamic and flexible, allowing for different views depending on one’s goals. Rather than seeing infrastructure as a fixed, ordered system, the stack approach treats it more like a web, open to different perspectives depending on your priorities.

This representation is therefore not a technical description of the digital stack as a whole, but rather an overview of the discourses about support for digital infrastructure, and of parts of the stack they refer to. The aim is to highlight key areas that are currently under discussion, rather than to provide a comprehensive breakdown of all the technologies and layers that make up the internet ecosystem.

The diagram shows that different discourses and proposals tend to address specific layers of the overall stack:

- The discourse on Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is primarily driven by the example of India’s Industrial Strategy, which is centered on generative foundations for public and private digital services and transactions. It allows public institutions to centrally manage a set of open application programming interfaces (APIs) that can be used by both the public and private sectors to develop services. The core pillars of digital public infrastructure typically include data exchange, identity and payment systems. European initiatives on “digital building blocks” include Digital Identity Wallets, Common European Data Spaces, or the Digital Euro.

- The discourse around cloud infrastructure addresses concerns about the current reliance on a handful of large players in the sector. Europe’s reliance on hyperscalers, largely controlled by American tech giants, threatens the self-determined use of technology by public institutions and businesses. This dynamic not only leads to a significant transfer of wealth to a few corporate actors, but also creates risks such as surveillance and technological weaponization. This layer combines software and hardware components and requires significant capital investment. Current European initiatives include Gaia-X, the Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI) on Cloud Infrastructure and Services and the European High Performance Computing Joint Undertaking.

- The discourse on semiconductors or chips operates at the critical intersection of digital sovereignty, supply chain security, and economic competitiveness. As a foundational input for modern digital infrastructure, the production and control of chips is pivotal to ensuring technological independence, particularly in emerging fields like AI and high-performance computing. However, Europe remains heavily dependent on foreign producers, particularly in the U.S. and Asia, where supply chain vulnerabilities were exposed during recent global disruptions. European concerns around exclusive access to these resources by tech giants to strengthen their dominance have for instance led to the recent Chips Act.

- Adjacent to this discussion is a discourse about supporting the foundational open software infrastructure of the Internet stack. This is mainly driven by concerns about the sustainability of the development and maintenance of the foundational software infrastructure that underpins much of the current digital ecosystem, the fragility of which has been exposed by recent cyber attacks. European initiatives include the Next Generation Internet (NGI) initiative and the German Sovereign Tech Fund.

- Our own calls for investment in public digital infrastructure mainly target the communication services and platforms built on top of the more basic infrastructure layers. Our proposal is driven by concerns about the lack of alternatives to dominant for-profit social media platforms and communication services, which create huge concentrations of power and wealth transfers and undermine public institutions and democratic societies. Similar approaches are proposed by the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure and Public Spaces.

In addition, there are two layers that have received less attention in the discussion, but which complement the overall picture.

- At the top is the layer of clients that provide access to the overall infrastructure. These include operating systems and browsers. Here the main concerns are about vendors acting as gatekeepers and an almost complete lack of European options. These concerns are embedded in discussions about competition enforcement and ex-ante market regulation (the DMA and its implementation).

- Connecting all these layers is the layer of protocols and standards that ensure the technical functionality and general design principles of the Internet (net neutrality, end-to-end principle, interoperability). This layer is less prominent in current discussions on digital infrastructure, but the openness of the Internet is supported by a wide range of actors, including the European Union. However, the multi-stakeholder model of internet governance is coming under increasing pressure as calls for digital sovereignty sometimes clash with the goal of maintaining a global, open and interoperable network.

Ultimately all of these layers are intertwined. Any strategy aimed at strengthening Europe’s digital infrastructure and bringing it more in line with democratic values and digital rights will need to address the full picture, based on a holistic understanding of this stack.

It follows that any strategy for investing in European (public) digital infrastructure must identify which combination of layers of the stack it is targeting, and which concerns – listed in the diagram on the left – it wants to address. The choice will largely depend on the underlying strategic objectives. Figure 2 maps three different sets of objectives onto the different layers of the digital infrastructure stack: (1) supporting digital public space, (2) sovereignty/independence/competitiveness, and (3) environmental sustainability.

From the perspective of ensuring the availability of alternative, public options that can guarantee a digital public space – which is at the heart of our proposals and a goal recognised in the EU’s Declaration of Digital Rights and Principles – the most relevant layers are communication services and platforms, and the underlying core infrastructure (primarily cloud and identity), as well as the foundational software layers. All of these will require public investment and other forms of support (e.g. through the strategic use of procurement rules).

If we shift the perspective to the objective of strengthening Europe’s digital independence, sovereignty and overall competitiveness, a slightly different pattern emerges. Here, communication services and platforms are seen as less relevant (this layer is left to the market). Instead, more attention is paid to the control of supply chains in the area of microchips and to the concentration of power in the area of gatekeeper platforms. It is also important to note that strategic objectives related to sovereignty and independence are likely to conflict with some of the design and governance principles in the protocols and standards layer.

From the perspective of ensuring environmental sustainability (which is likely to be a parallel or secondary objective in most scenarios), the main areas for intervention are at the level of the core digital infrastructure (especially cloud storage and compute) and, to a lesser extent, at the level of microchips and clients.

Again, it is important to recognise that without changes to the operating logic of the whole stack, interventions at any particular level are likely to be treated as efficiency gains and are therefore unlikely to be effective on their own. This points to a wider problem with interventions in this area that seek to shape the technological environment based on societal objectives. Such interventions need to combine public investment with specific conditionalities. These need to ensure that investments, as well as the enforcement of competition rules, do not simply replicate – on a smaller scale or under different ownership – existing systems and their negative externalities.

More fundamentally, any attempt to design a strategy to strengthen Europe’s digital infrastructure so that it addresses concerns about democratic values, competitiveness and sustainability will need to operate at all the levels discussed above.