At the last Open Future Session, our speaker was Olivier Schulbaum, the co-founder, President and Head of R&D of Platoniq. Olivier introduced himself as a “Creativity and Democracy enabler.” Olivier and his collaborators have been developing services at the intersection of culture, openness and democratic participation for over twenty years. We asked him to share his experiences creating and maintaining open initiatives and platforms, and his views on where open should be going.

“Through the platforms that we are building, we want to make sure that the open movement is connected with social movements and local or national democratic governance”

said Olivier at the very beginning of the session. What makes Platoniq’s approach special is that they do this through a specific approach to user experience design, which Olivier calls “political user experience (PUX).”

This is also a perspective founded strongly on a social and solidarity economy, based on respect for diversity and care for fair and just relationships. In this way, the commons become strongly connected with social justice causes.

The political user experience perspective is a fresh take on openness, which traditionally has been secured through other means: voluntary legal tools, or state policies. Olivier even mentions gamification as a key perspective, quipping that democracy should be taken very seriously, but then also can be fun – if the political user experience is properly designed.

Olivier highlighted Platoniq’s approach by talking about two platforms that the organization is maintaining. The first one is Goteo, an open crowdfunding platform that “crowdfunds the commons.” The platform, running now for almost a decade, has crowdfunded projects worth over 14,5 million Euros, with a success rate of 87% of projects funded. Goteo is also a “crowd benefit” platform: the financing of projects by backers is structured in a way that also secures value for the whole society (as opposed to traditional crowdfunding, where the value is generated just for project owners and backers).

One of the means to do that is an open licensing framework that is the heart of Goteo, requiring projects to openly share different types of outputs. The openness of results is an important signal to backers, one that signals the social commitment of the project. Another means is the multitude of ways that backers can support projects – not just with money, but also talent, skills and time. In this sense, the platform is based on principles of the circular economy. Olivier says that Goteo is not really about money and funding – it’s about community building that takes into account the financial needs of communities. So measuring social value and impact – the Goteo team is right now working on a measurement framework for this – is just as important as the financial side.

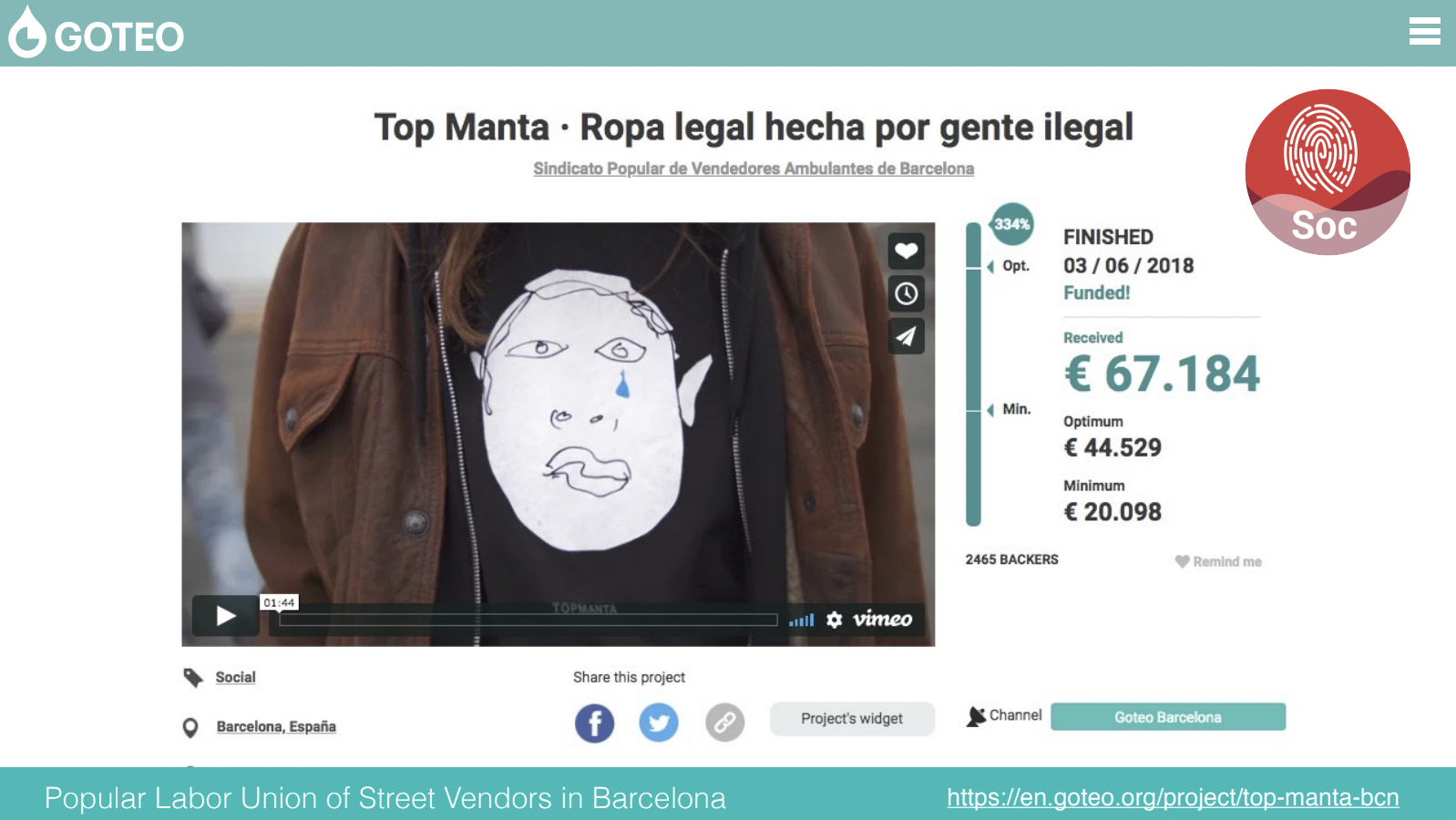

Goteo is also a platform for social, democratic change. Olivier highlighted one project that illustrates this approach, that of Top Manta, a cooperative of Barcelona’s street vendors – who are mainly immigrants, many of them illegal. Goteo crowdfunding helped them establish an association functioning as a vendors’ union, which ultimately became a cooperative. It also funded a communication campaign that made more visible the challenges that the vendors face.

In this way, Goteo not only provides financing, but supports people with no legal status to establish themselves as social entrepreneurs, and to develop means to support themselves as a community. The crowdfunding investment was returned many times, as jobs were created. But there’s also social value that’s harder to measure, related to participation, a sense of empowerment and social justice.

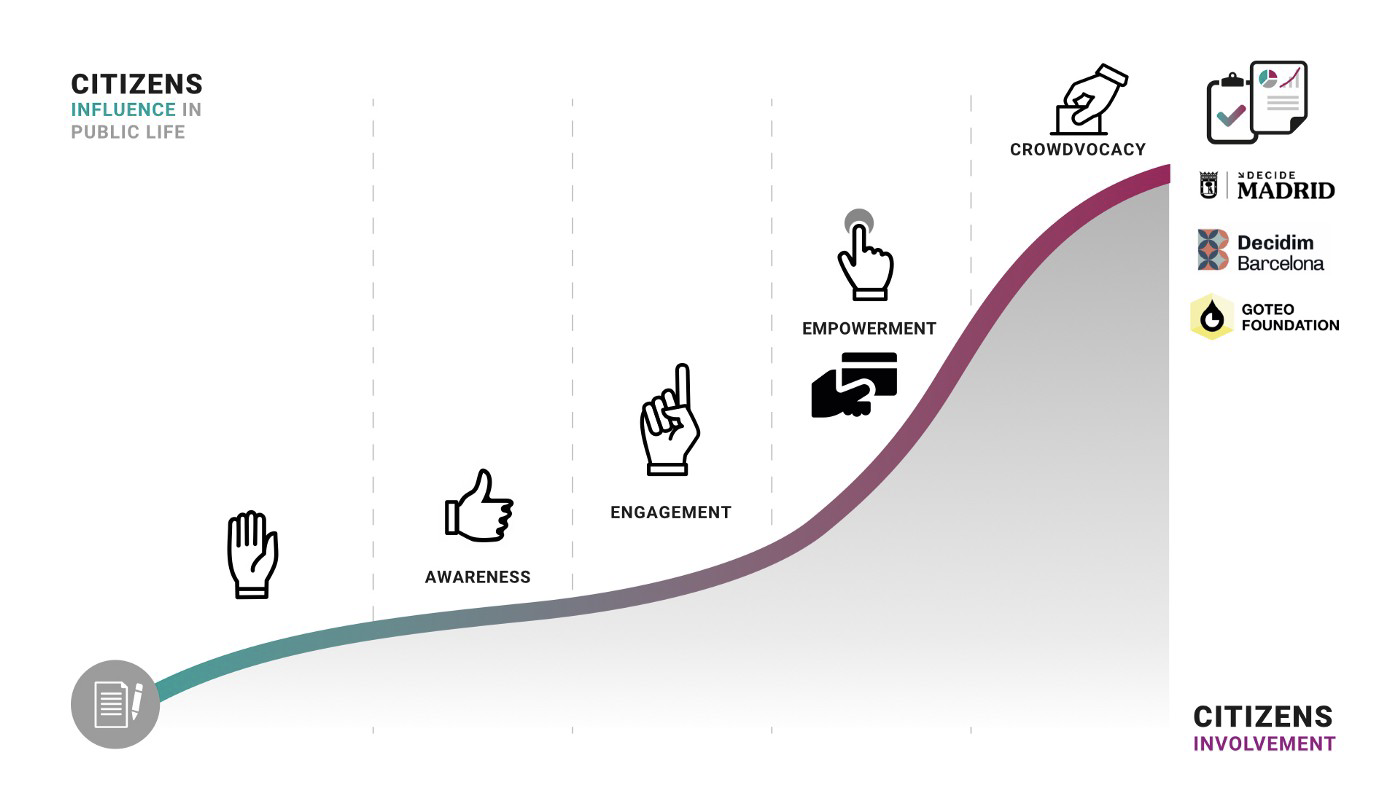

The engagement ladder of crowdvocacy

Decidim is open-source software and is being managed, in the spirit of open-source initiatives, as a distributed, collaborative project. Olivier highlighted the specific nature of the platform, which on the one hand, by virtue of being global, allows improvements to be immediately shared across all the cities using it – multiplying social value. At the same time, platoniq, as an active member of the Decidim community, pays attention to different local cultures of participation – there is no “one size fits all” software solution that guarantees civic participation.

Another important aspect is the governance of Decidim initiatives – it is governance and not software code that guarantees respect for social values and justice. The Decidim project itself is organized in a democratic way. This connects with the specific nature of Decidim as a global project that pays attention to localities – democratic governance is the means for ensuring this works smoothly.

For Olivier, this means that the social contract needs to be built on top of both the software code and any legal licensing infrastructure. And this is where the idea of political user experience becomes clear: Platoniq designs not just functional online platforms, but also democratically governed communities and initiatives. And they are also engaging public institutions in lasting partnerships that both strengthen local democracies and make civic projects more sustainable. For Goteo, co-funding by public bodies is an important mechanism. And for Decidim, the platforms serve as civic interfaces for municipal governments.

Looking at Goteo initiatives, their holistic nature is both impressive and inspiring. As Olivier demonstrated, platforms built by Goteo are strategically designed, not just using the standardized toolsets of open licensing or civic participation projects, but additional elements, such as social and solidarity economy principles, or user experience design methods. It feels that Goteo is working not just with one type of tool that ensures openness, but is building a whole operating system for open platforms.

It has been commonplace in the open movement to talk of the need to include social values on top of the traditional “open stack”, to pay more attention to social justice or equality. And the way open projects either support those values – or fail to do so. But often, this does not result in tangible outcomes. With Goteo’s project, the feeling is different – that these values were translated into specific designs for both online services and social institutions, that can really be both democratic and open.

Olivier challenged our community by saying that we lost the ethical feeling – the vision of an open Internet is not translated today into a vision of a more just and egalitarian digital society. “We need to be democratic first, and then open,” Olivier told us, and it sounded like a call to action.