On the 10th of November the European Commission adopted two documents that have at their core the ambition to create so-called Common European Data Spaces: the recommendation on a common European data space for cultural heritage and the Digital Europe work program 2021-2022. Both of them aim to bring into practice the concept of Common European Data Spaces that was first proposed by the Commission in its 2020 European Strategy for data.

For anyone who had hoped that these documents would shed more light on what exactly the Commission has in mind when it talks about common data spaces, these documents will be disappointing as they do not offer significant new clues.

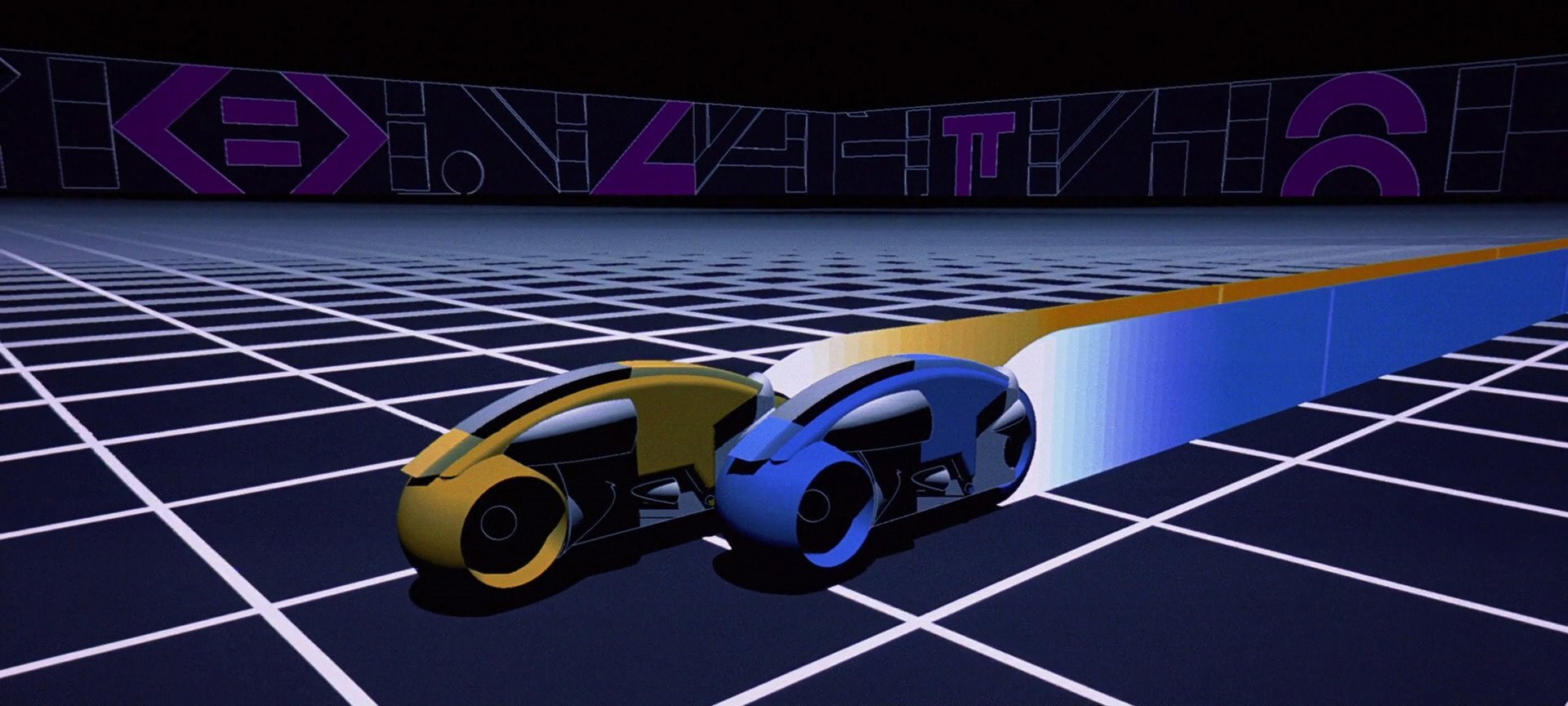

For me, the term “Data Spaces” still evokes visions of blobs of data situated in cartesian space that can be accessed by navigating through such space — low-resolution predecessors of contemporary visions of the metaverse.

But in the dry prose of Commission proposals, the concept of Common European Data Spaces is much more elusive. By establishing such spaces the Commission aims “at overcoming legal and technical barriers to data sharing across organisations, by combining the necessary tools and infrastructures and addressing issues of trust, for example by way of common rules developed for the space“[1]. How this will actually work and what the necessary tools are is largely left to the imagination of the reader — or more precisely to those organizations considering bids for the €400M in funding under the Digital Europe work program.

This Digital Europe work program, which will provide funding for Common European Data Spaces for pretty much every imaginable aspect (the green deal, smart communities, mobility, manufacturing, agriculture, finance, tourism, skills, cultural heritage, health, languages and public administration) mentions the term Data Spaces 220 times but does not provide anything resembling a definition. The closest it comes to this is by declaring that they will be based on a “large-scale modular and interoperable open-source smart European cloud-to-edge middleware platform” [2] —that is yet to be developed.

Even the recommendation on a Common European Data Space for cultural heritage — of which one could reasonably expect a clear definition of the idea — remains relatively vague and does not offer more than a recursive definition of the concept: according to the recommendation, Europeana is at the core of the emerging Common European Data Space for cultural heritage which is constituted by the sum of all the data made available through the Europeana initiative in compliance with its various frameworks (“including the Europeana Data Model, RightsStatements.org, and the Europeana Publishing Framework”).

I have spent a good deal of the past decade architecting, developing, refining and implementing these very frameworks and developing Europeana’s data governance model. If the work I have done with Europeana and its partners over the past 15 years has indeed been at the vanguard of building Commons European Data Spaces, then what insights does it provide about the design of such a data space?

Five things I have learned about data spaces

So here are a few things that I have learned working with Europeana and its network partners on building the foundations of what is now being called the Common European Data Space for cultural heritage:

First of all, building Common data spaces is hard. Even in a sector where there is very strong alignment on the intended outcome (nearly everybody would like to see the sum of all of the EU’s cultural heritage accessible to everyone online), it is difficult to agree on a way to get there. Institutional self-interest, conflicting demands from funders are just some factors, due to which building for the common good is rarely the primary objective.

As a result, shared data spaces require stewardship (at least initially) by organizations committed to something bigger that their own institutional self-interest. There also need to be incentives (financial, regulatory or reputational) for data holders to contribute to the common project. In the case of the Common European Data Space for cultural heritage, the Europeana Foundation has worked hard to become such a steward. Also, financial incentives from the Member States – tying digitization funding to the availability of the resulting data via Europeana in line with the principle public money = public access – have played a very important role.

As the name implies, Common Data Spaces should function as commons: building Common Data Spaces means building a shared resource that should in principle be available to everyone and that is stewarded in the interests of contributors and the public alike. To succeed, common data spaces must be non-extractive: instead, they should be cumulative and strive to become something that is more than the sum of individual contributions. This also requires rejecting the competing vision of Common Data Spaces functioning as markets.

In the long run, common data spaces should be multi-nested. They should not be dependent on a single steward. The goal must be to have multiple stewards that ensure that the health of the data space does not become the institutional responsibility of an individual entity. In the case of the Common European Data Space for cultural heritage this would mean that it is time for additional stewards to emerge. Candidates for this include the Wikimedia projects such as the Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata, the newly established Flickr Foundation which aims to be a very long-term steward for the Flickr Commons or the Internet Archive[3].

Finally—and maybe most importantly—Common Data Spaces should not be seen in isolation. As the Commission notes in the Data Strategy “Data spaces should foster an ecosystem (of companies, civil society and individuals) creating new products and services based on more accessible data“[4]. Data spaces should be seen as one element of a larger ambition to build Digital Public Spaces that connect public institutions, civic initiatives, citizens and the private sector through data-flows. Common Data Spaces that are stewarded as commons and that build on public digital infrastructures are one of the most important building blocks for Europe’s ambition to build a digital space that reflects European values.

Footnotes

- European Strategy for Data, p15 – the concept of Commons European Data Spaces was first outlined in the 2020 European Strategy for Data.^

- Digital Europe Work Programme (2021-2022), p.22^

- In this context the rightsstatements.org initiative that the Commission mentions as an element of the Common European Data Space for cultural heritage, which has been jointly developed by Euroepana and the Digital Public Library of America, explicitly aims at facilitating data exchange on a global scale. This shows the potential for Common Data Spaces to extend well beyond Europe alone.^

- European Strategy for Data, page 5^