In her last post, Friction and AI Governance: Institutional Intermediaries, Nadia looked at how institutional intermediaries can support participatory governance. In this article, she shares learnings from facilitating a citizen assembly with Algorights to investigate local participation concerning the AI Act. You can read more about Nadia and learn about our fellowship program here.

This past June, I was a facilitator with Algorights at the Jornadas DAR. Jornadas DAR is an event organized by civil society organizations in Spain that focuses on the intersection of human rights, feminism, and technology. This year’s main concern was the issue of AI and the impact of facial recognition systems, which ties in closely with the current governance process around the AI Act.

In the previous blog, I wrote about how intermediary institutions need to ground translational governance processes in national or local contexts by creating networks and raising awareness. During the Jornadas event, I tried doing just that. My role was to facilitate a workshop that would generate a statement, recommendations, or demands to influence the creation of the European AI Act. The workshop participants were to analyze the effects of AI facial recognition and its impact on fundamental rights such as privacy, assembly, or anonymity.

Another underlying objective was to develop best practices for running a citizen assembly. The workshop gave me an idea of how consulting citizens, grassroots movements, and civil society in developing transnational laws that would be implemented universally across the EU could look like.

Citizen assemblies take many forms, and there are no definite and fast rules or indicators for making them successful. For this assembly, I aimed to go beyond awareness raising and examine what concrete outputs could come from such a gathering. In the case of this particular workshop, the result was a formulation of an advocacy message that all participants felt confident about putting forward.

Guideposts and Insights

When designing the activities for a session, assembly, or workshop, I always make strategic decisions about the tone and shape of the following activities. The below guideposts are meant as support for designing such activities and deciding your priorities in setting up the flow and outputs of your assembly.

Scaffolding

Participants of the assemblies are often individuals who come from different walks of life and have a range of experiences (because of work or otherwise) related to the overarching theme of the assembly. This diversity can sometimes make it difficult to see how to reach the same position or side. For example, a lawyer and an activist who both advocate for fundamental human rights will use different frameworks, language, and references to state their position and argue their points. This means it might take longer to connect the dots within the conversation to see where they agree and where they disagree. Working with diverse experiences and approaches in the room can make activities time-consuming. This can be difficult to balance when we want participants to feel free to share their experiences and ask questions. The proposed method is one that I used in the citizen assembly and have used in the past to ensure that participants have a common understanding of the discussed issues from the start.

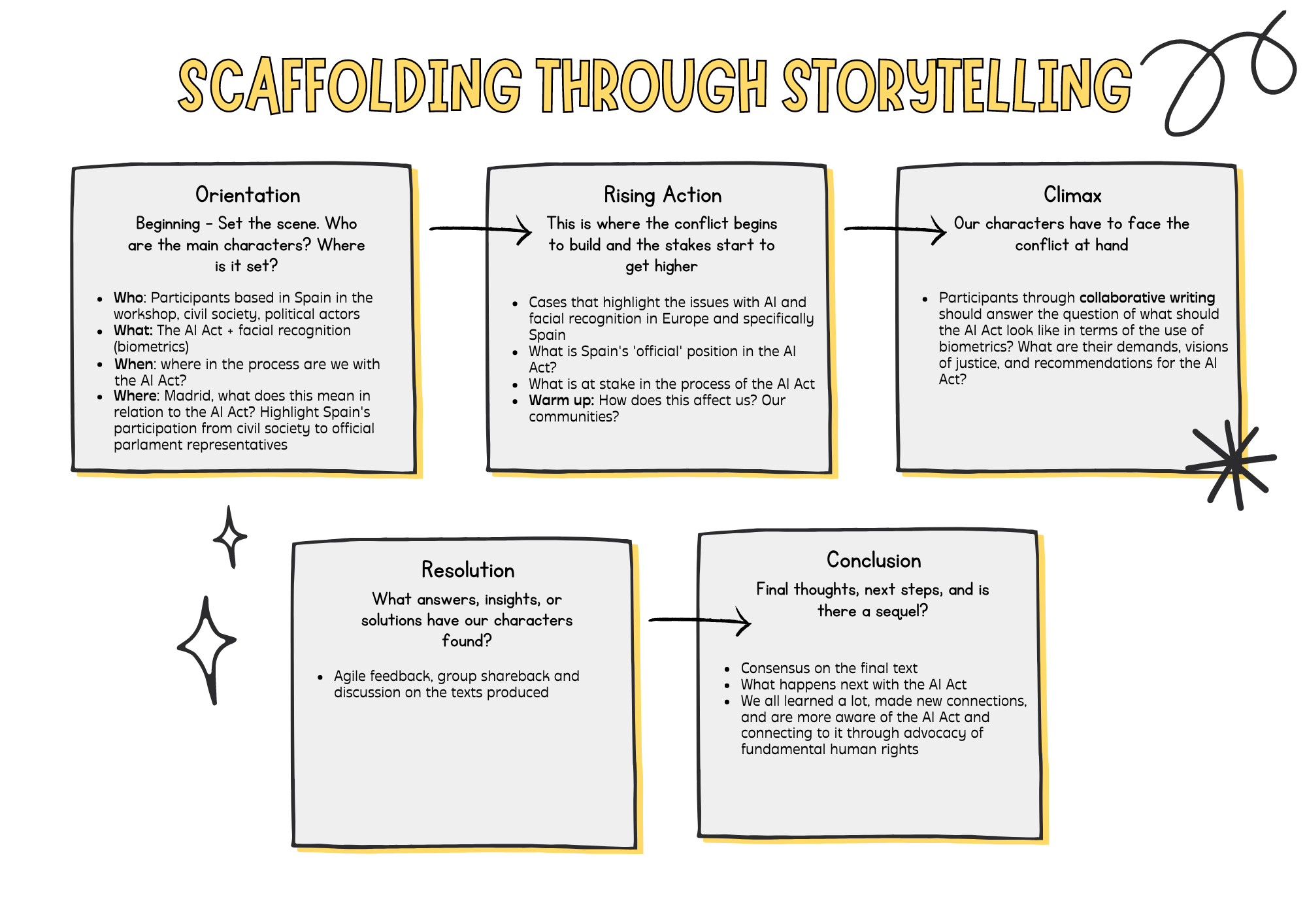

Scaffolding refers to a pedagogical method where learning is broken up into activities that get progressively more complex with each activity. Additionally, learners can make mistakes, ask questions, and ‘play’ or ‘experiment’ with a topic.

I approach scaffolding by thinking about the blocks of information that participants need from a narrative perspective and ask what needs to be set in place for me to begin the narrative and for the participants to meaningfully engage with it and write their own end of the ‘story.’ How do I start from the beginning if someone is unfamiliar with the topic? Who are the main actors? What is the conflict that needs to be resolved? Where should I exercise narrative economy?

For the citizen’s assembly, the core facets of the setting meant an overview of biometrics, facial recognition, and the process and possible outcomes of the AI Act. In terms of the actors, this meant reflecting on place, i.e., who are the permanent representatives for Spain in the EU Parliament? What has been their position on the AI Act? Setting the scene can happen through a presentation, bringing in experts, showing case studies, etc.

How did scaffolding translate into an agenda? The workshop’s objectives to develop best practices for citizen assemblies and facilitate the creation of a text were ambitious, given that the run time in total would be two hours. My approach was to help me trim and create an environment where language, facts, and ideas were approachable and allowed participants to play and have agency around the topic at hand. In sharing I hope to support the larger community around ethical AI to approach facilitating or creating such spaces with more confidence and that we have a more open approach to sharing our work:

Introduction (10 min)

Explain the objectives of the workshop and give an overview of the activities.

Status of the AI Act (15 min)

Give an overview what the AI Act is, the governance process, stakeholders, and expected outcomes (presented by a legal expert working on the AI Act). Then present an overview of AI Biometrics as it relates to the AI Act with examples of its use in Europe.

Warm up (15 min)

Ask participants how profiling impacts their everyday life and how facial recognition technologies might magnify this impact.

Reflecting on Our Rights in Working Groups (45 min)

Divide participants into groups, each group focusing on rights that might be put at risk in the AI Act such as the right to dignity, privacy, liberty, assembly, and presumption of innocence.

Each group is to produce a statement, recommendation, or demands as to what shape the AI Act should take. Working groups as materials should be given a brief explainer on the definition of the right they are working with and concrete examples of what exercising this right looks like in practice.

Using the Warm-up to Begin the Conversation

Because of the short length and ambitious outcomes expected from the workshop it was important to start the conversation around the AI Act from the warm-up. When using the warm-up to get participants into the topic, it can be helpful to think of some approachable and simple questions to get participants to jog their brains on the topics they will explore. Also, it’s a straightforward activity that allows participants to easily and quickly draw on and share a bit of their prior knowledge. I facilitated this session in person and used a whiteboard where participants could post their answers and read the answers of the larger group. I asked the following questions:

- How do surveillance and profiling based on your physical appearance affect your everyday life? How have you seen it impact others?

- How does it affect your quality of life?

While the workshop aimed to center biometrics in the AI Act, the harm that biometrics reinforce is generally around profiling and mass surveillance. The questions were meant to make the issues around biometrics more tangible, accessible, and relatable to each participant’s experience. Writing a question like ‘How do biometrics and AI affect your everyday life’ would be too broad and perhaps even difficult to answer, depending on each person’s awareness or idea of biometrics.

Making Rights Concrete

The first insight into supporting participants was the necessity of grounding the rights they were to cover with tangible experiences and cases. Consider the right to dignity: dignity is a word that captures many meanings and implications. However, for a relatively short workshop, it was essential to use a specific reference to the Charter of Fundamental Rights and concrete cases of its use.

The right to dignity is described simply as: ‘Human dignity is inviolable. It must be respected and protected.’ However, this sentence does not give enough context to work with the concept of dignity itself. For the purpose of this workshop, we used the following examples of how this right to dignity can be used:

- Member States have to enact measures that “protect the dignity of victims during questioning and when testifying” before courts (Art. 18 of the Victims Directive 2012/29/EU).

- Border guards have to “fully respect human dignity, in particular in cases involving vulnerable persons” (Preamble of the Schengen Borders Code, regulation 2016)

The aim of providing these two examples was to help participants understand when and how the right to dignity should come into effect to protect human rights and, essentially, human life. During this facilitation session, we focused on cases and concrete situations that demonstrated where and how rights can become concrete tools for people to advocate for themselves. For the resulting recommendations and texts to resonate and be applicable, we needed participants able to explain jargon from the AI Act as well as phrases and language used for human rights advocacy.

Participatory Writing

The participants were given a broad task of producing a text, whether it was recommendations, demands, or statements on what form the AI Act should take regarding rights that were at risk within it. I facilitated this activity by developing a series of prompts that participants could respond to:

- Why is this right important? Why do we demand it should be protected?

- How is protecting this right essential to preserving a more just society? For our well-being as a community?

- What does the preservation of this right look like?

Each group was given a paper copy of the presentation that contained the case studies, definitions of each right, and tangible scenarios where those rights could be demanded or when they had been violated. Using these materials, they were then asked in group to respond to the prompts, discuss, and produce a text.

Additionally, the session was supported by facilitators and experts in the room who were able to walk around, provide support, and talk participants through if there was a writing block.

Visual, Agile Feedback Systems

During the feedback session, participants could walk around freely and look at the work of each working group. When they agreed, they could add a green dot; when they disagreed, they could add a red dot; when confused, they could add a blue dot and ask clarifying questions or give constructive feedback through post-its.

Through this system of dots, which could have been other stickers or emojis, participants can use quick visual cues to give feedback and encourage participants to approach each other’s work with constructive and curious attitudes. At the end of a workshop, using visual feedback systems is helpful because participants have already been tired; working with emojis, and stickers and some free movement help manage everyone’s energy and make participation more accessible.

Intersectional Approach

Intersectionality focuses on how different matrices of domination, i.e., different forms of structural inequalities stemming from class, geography, gender, etc., create unique forms of oppression that are often invisible to those without the same situated experience. When talking about the harms and risks of AI, especially concerning facial recognition and biometrics, those most vulnerable to these technologies are people on the move. Within the workshop were several participants, such as from Asociación Sobre los Margenes and Exmenas, who actively support efforts for better treatment for marginalized youth, people on the move, and safer borders. Their participation was a cornerstone to producing some of the most concrete and tangible recommendations. As reflected in the Design Justice Principles, the idea and practice of including the people most impacted by design and technology is crucial in such a process. It goes beyond diverse participation by allowing communities to advocate for themselves in ways that fundamentally shift, change, or completely dismantle the systems and technologies that reproduce harm and discrimination.

Conclusion

I believe intermediary institutions are important in raising awareness, creating networks, and ultimately supporting and facilitating participation from local and national contexts. This workshop was a test to see how that might look working with citizens and residents. The AI Act will impact all EU countries and become law once passed, so I focused on making AI real for everyday people and creating pathways for them to voice, participate, and shape laws created for them but largely without them. Below, you can see the effects of our work.

It was beneficial to have a variety of experts actively working with the AI Act while defending human rights for people on the move present in the room. Working with legal experts and human rights defenders who can immediately contextualize the importance or the use of human rights or the abuses of border technologies in transnational governance spaces and on the ground was extremely useful, especially given the limited time. For the resulting recommendations and texts to resonate and be applicable, we needed participants able to explain jargon from the AI Act as well as phrases and language used for human rights advocacy.

Ideally, the workshop I facilitated would have at least three different moments to develop, debate, and create consensus on the text produced. As for what this might look like on a larger scale, it is becoming increasingly evident that digital and information literacy is integral to creating resilient democracies. AI technologies are moving far faster than we had imagined, and people’s imaginations filling the gaps in understanding how AI works. There is a clear need for intermediary institutions to raise awareness and create space for lifelong learning and dialog. Otherwise, the danger is that the present narrative of AI as inevitable or all-seeing becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Citizen Consultation Workshop Results

The workshop lasted for about two hours, and in that time, our working groups were able to produce the following text (translated from Spanish to English):

Right to dignity

We defend the right to dignity because it is the mother of all human rights, recognizes the value of human life, is inalienable, and allows for self-determination and the free development of the personality. We, therefore, call for

- Banning biometric recognition in public spaces.

- Banning biometric categorization and inferences[1].

- Guaranteeing the explainability of algorithms and the right to object to them.

- Ensuring disclosure of the functioning of automated systems while taking care not to make citizens responsible for ensuring compliance.

- We, therefore, demand the creation of a Data Ombudsman’s Office.

Right to privacy

We want a future with a culture of privacy rooted in legal principles to:

- Guarantee privacy through the control of our personal data to prevent misuse or unauthorized use

- Preserve security in telecommunications

- Protect different vulnerable groups, avoiding bias, prejudice, and discrimination.

We want to make privacy the cornerstone of digital care <3

Right to Liberty

The current system perpetuates the lack of freedom. We must avoid using AI as a tool for mass perfection of the system of control and repression. Transparent processes are needed to eradicate misuse as well as the participation of the communities in which these technologies are applied and affected. Involve them in defining, maintaining, and making this process accessible.

Right to Assembly

The right to assembly is fundamental to preserving democracy.

- Right to demand, to self-organize, to freedom of expression, and to the legitimate use/enjoyment of occupying public space.

- It acts as a basic instrument against authoritarianism.

- It promotes a critical society linked to its social reality.

How can it be preserved?

- By creating a binding citizens’ legislative initiative at the European level.

- By funding committees for direct and inclusive citizen representation of society as a whole.

- By developing a citizens’ audit instrument

- By promoting and raising awareness of the right to assembly through education / encouraging more collective meetings.

- Through more decisive power exercised at a local level in EU legislation.

- By considering regional differences and particular needs of each territory (borders…) when proposing new regulations.

If none of that works, we also propose to burn it all down. 🔥🔥

Footnotes

- In the discussion with the other groups, there is debate, and it is agreed to add the exception of allowing it for scientific research uses in health.^