Undermining the foundation of open source AI?

Today, the European Parliament’s LIBE and IMCO committees adopted their long-awaited report on the European Commission’s proposal for an AI law. The report[1] is expected to become the basis for the European Parliament’s negotiations with the Commission and the Council once it is adopted by the plenary in early June this year.

The discussions in the European Parliament have resulted in a text that significantly amends and improves the Commission’s proposal. The text adopted today includes a number of additional safeguards, fundamental rights protections, and restrictions on the use of AI that a broad coalition of civil society organizations had advocated for. All in all the text adopted today reflects a more cautious approach to AI than was present in the original proposal. It also departs from the regulatory technique underlying the Commission’s proposal — the regulation of specific (high-risk) uses of AI — in favor of an approach that also regulates AI technology as such.

As we have previously highlighted, this change in approach has raised questions about how the AI Act would affect the open source development of AI systems. The remainder of this analysis will take a closer look at how the provisions contained in the report adopted today would interact with the development of open source AI systems. This analysis builds on our earlier analysis of the Commission’s proposal and the Council’s general approach, which we published last December[2]. In addition, a final section of this document also highlights a new proposal related to the transparency of data used to train generative machine learning (ML) models.

Safeguarding Open Source AI Development

As we have argued previously, it is crucial for the EU legislator to establish a regulatory framework for AI that achieves the dual objective of mitigating the potential harms caused by the use and availability of so-called AI systems, while at the same time safeguarding the possibility to develop AI systems and components of such systems as open source software. By including general-purpose AI systems within the scope of the Act, the Council risked creating a chilling effect on the open source development of foundation AI models/systems. This is contrary to the public interest goal of encouraging open source development of this important technology. Open source AI systems provide an important check on the tendency of large technology companies to develop and deploy AI systems as black boxes. In the months since the adoption of the Council text, this ability of open source development to serve as a check on corporate closed-source practices has become increasingly clear.

An Open Source Exemption Riddled with Exemptions

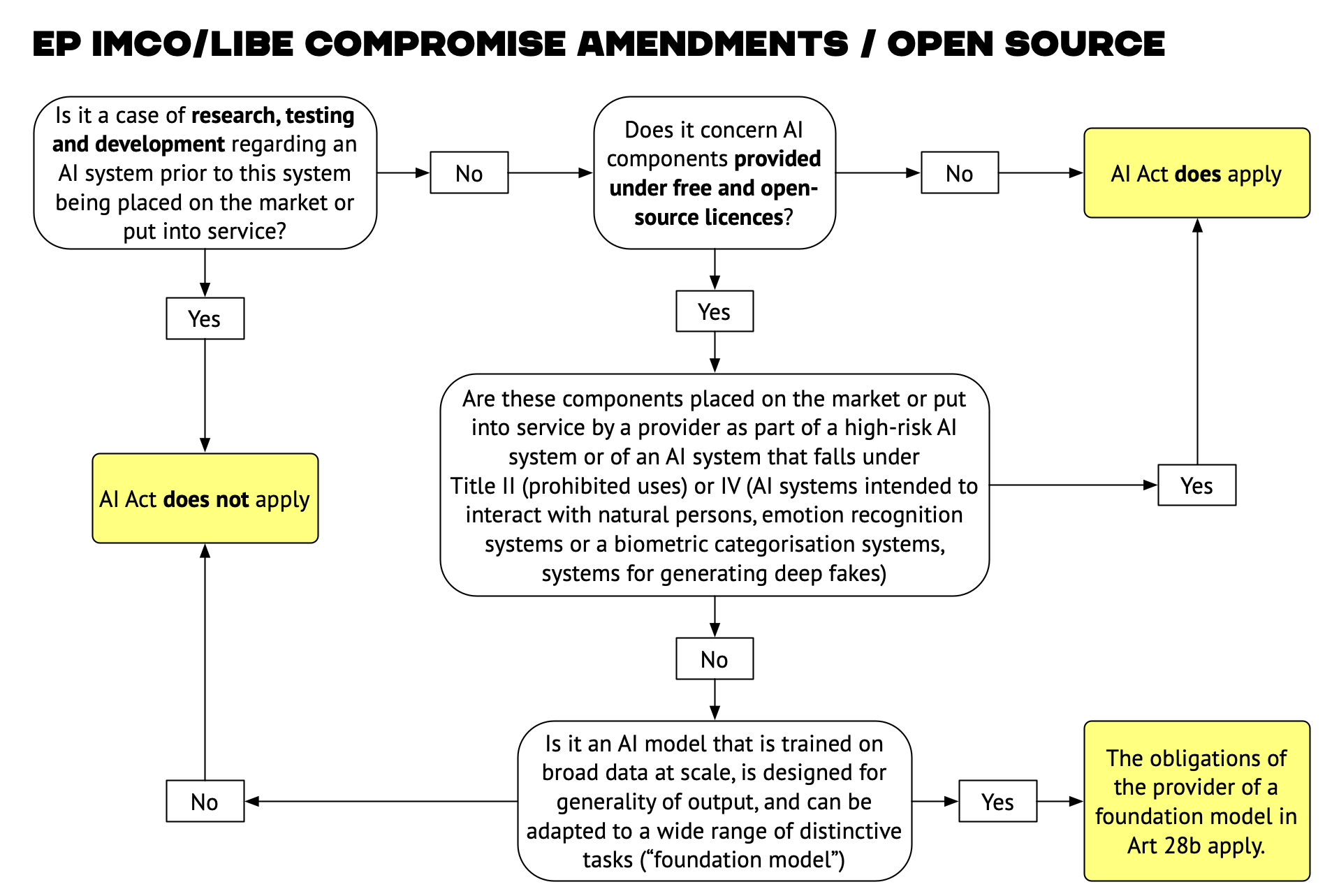

Neither the Commission’s original proposal nor the Council’s general approach contains any provisions on open source development of AI systems. The text adopted today in LIBE/JURI departs from this line and includes a limited exception for “AI components made available under free and open source licenses”. Together with the exception for “research, testing and development”, this exception is intended to ensure that open source development of AI systems remains viable in the EU.

As shown in the schematic overview above, both the research exception and the open source exception are limited in scope. In particular, the research exception (in Art.2(5d) of the EP text) does not cover “testing in real-world conditions”[3].

The open source exception (in Art.2(5d) of the EP text) has another set of limitations. It cannot be invoked for AI components that are “placed on the market or put into service by a provider as part of a high-risk AI system or an AI system that falls under Title II or IV”. These restrictions ensure that open-source AI development cannot be used as a loophole to evade the law’s core regulatory goals. In the case of high-risk AI systems or systems used for prohibited practices (Title II), and systems used for certain problematic practices such as emotion recognition, deep fake generation, or that interact directly with human beings, the rules of the AI Act also apply to open source systems.

Finally, the open source exemption “does not apply to foundation models,” which are defined in the text as “AI model[s] that [are] trained on broad data at scale, [are] designed for generality of output, and can be adapted to a wide range of distinctive tasks.”

Providers of foundation models (including developers “providing models under free and open source licenses”) must comply with a number of specific requirements listed in a new Article 28b and discussed in the next section below.

Taken together, these restrictions significantly narrow the scope of the open source exception. There appears to be very little room for the development and provision of AI systems that are neither foundation nor interact directly with natural persons. As a result, it is questionable whether the execution covers anything other than components that are not functional in themselves, and this means that open source developers in the EU will face a significant regulatory burden that will be very difficult to comply with.

Requirements for Foundation Models

The new Article 28b, which imposes obligations on suppliers of foundation models (including models “provided under free and open source licences”), reflects growing concerns about the wider — and so far largely unregulated — availability of such models. The release of Microsoft’s AI-powered Bing, GPT4, and Google’s Bart all occurred while the Parliament was working to find the compromises that led to the text adopted today, and this is reflected in the approach. For foundation models, the Parliament’s text includes requirements to:

- Demonstrate risk mitigation strategies and document non-mitigable risks;

- Use only data sets that are subject to appropriate data governance measures, taking into account the suitability of data sources and potential biases;

- Design the model to achieve “performance, predictability, interpretability, corrigibility, security, and cybersecurity throughout its lifecycle.”

- Use state-of-the-art methods and applicable standards to reduce energy and resource consumption, increase efficiency, and measure and report energy and resource consumption.

- Prepare comprehensive technical documentation and user manuals to enable downstream suppliers to meet their obligations.

- Establish a quality management system to document compliance.

- Register the foundation model in the EU database for high-risk AI systems;

- Make the technical documentation available to the national competent authorities for a period of 10 years after their foundation models have been placed on the market or put into service.

In addition, providers of generative AI systems[4] must:

- comply with the transparency requirements of Title IV[5];

- train, design and develop models to ensure “adequate safeguards against the generation of content in breach of Union law […] without prejudice to fundamental rights, including freedom of expression”; and

- without prejudice to existing copyright law, “document and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the use of training data protected under copyright law.

Taken together, these obligations create a fairly significant compliance burden for providers of foundation AI systems that will be very difficult to meet for all but the largest players. As currently written, this article threatens to create regulatory moats around large tech companies that can afford to comply with these rules, while making it impossible for smaller players (both open and closed source) to operate in this space. The obligations established by Article 28b seem to assume that all providers of foundation models are large companies with almost infinite resources, while the evolution of the generative ML space over the last year has shown that this is not the case, and that there is great potential for developers of open source AI systems to break the dominance of today’s dominant platforms. But this will only happen if the AI Act does not make AI development by smaller players impractical.

Deployed at scale vs made available as code

There are two problems with the text’s treatment of foundation models. The first concerns the obligations placed on suppliers of such models: the obligations are both too broad and too vague (there are 6 instances of the word “appropriate” in Article 28b alone) for meaningful compliance. The second problem is the indiscriminate application of these obligations to models regardless of whether they are deployed at scale or simply made available on open repositories.

Here, the text adopted by the Parliament is ambiguous . While Article 28b states that the obligations apply to foundation models “regardless of whether it is provided as a standalone model or embedded in an AI system or a product, or provided under free and open source licences, as a service, as well as other distribution channels.”, the corresponding Recital 12b states that “neither the collaborative development of free and open-source AI components nor making them available on open repositories should constitute a placing on the market or putting into service”.

As a result it is not clear whether developers of free and open source foundation models (“open-source AI components”) who collaborate and publish them (“make them available”) on open repositories would have to comply with the requirements from Art 28b.

While such an ambiguity in the text is not helpful, there is still an opportunity to fix it in the upcoming trilogue negotiations, for which the EU Parliament’s text, with all its shortcomings discussed above, provides all the relevant building blocks.

A two tiered approach for Foundation Models

What should an approach to foundation models that preserves meaningful space for open source AI research and development look like? First, it seems important that open source models are included in the scope of provisions that apply to foundation models. However, they should not be burdened with the same obligations as those applied at scale.

It would therefore be much more appropriate for the final version of the AI Act to define a set of baseline requirements that apply to all foundation models (including those made available under free and open source licenses), and a set of additional obligations that apply to models that are deployed at scale or otherwise made available on the market for commercial purposes.

- The baseline requirements should include transparency of training data and model characteristics, documentation of risk mitigation strategies and non-mitigable risks, and provision of technical documentation and user guides.

- For models that are deployed at scale or otherwise made available on the market, the other obligations introduced in the EP text should apply, although some of them — such as the design requirements — should probably be less prescriptive[6].

Creating a clear distinction between models that are provided under free and open source licenses and those that are commercially available or widely deployed (including open-source models that fall into this category) would provide more room for open-source development. This distinction would capitalize on the strengths of open-source development, such as code transparency, data availability, and public documentation of functionality. By merging these elements with key accountability measures like risk management and documentation, it will be possible to maintain a balance where providers of open source AI systems are not overwhelmed with compliance duties that are typically suited for larger entities.

Interestingly, this insight is reflected in recital 12c of the Parliament’s text — “Developers of free and open-source AI components should however be encouraged to implement widely adopted documentation practices, such as model and data cards, as a way to accelerate information sharing” — but this insight has yet to be adequately reflected in the operative provisions of the text.

A note on transparency

As explained above, the EP text also introduces a new transparency requirement related to the use of copyrighted works for training generative ML models. While this addition makes a lot of sense from a pure copyright perspective[7], its limitation to copyrighted training data also shows that the AI law as a whole lacks meaningful transparency requirements for training data.

Given the overarching regulatory goal of mitigating risk and increasing transparency in the development and deployment of AI systems, one of the biggest omissions in the act is the lack of a general transparency requirement for training data that applies to all types of AI systems (not just generative ML models) and all types of training data (not just copyrighted data). Such a requirement will address privacy concerns about the use of personal data, and it will face objections couched in the language of trade secrets. While privacy concerns must be addressed, any objections based on trade secrets should be rejected. Given the risks associated with the development and use of AI, transparency about the ingredients that go into AI systems should be a top priority — after all, this is a regulatory approach that has proven effective in many other areas where safety is a concern, such as food safety[8].

Footnotes

- As of writing the report is not available yet, but the European Parliament has published a document containing the consolidated compromise amendments that have been adopted.^

- Note that this analysis heavily relied on the concept of General Purpose AI systems (GPAI). The inclusion of GPAI in the scope of the act meant that open source development of such systems would be in scope. Provisions on GPAI — while still present in the text adopted today — play a less important role when it comes to understanding the impact on Open Source AI development as open source development is now explicitly addressed in the Parliament’s text.^

- This clarification addresses the concern raised by civil society organizations that otherwise the research exception could become a loophole where AI is used in pilot projects affecting the fundamental rights of people without the legal safeguards otherwise provided by the AI Act.^

- Defined in the article as “AI systems specifically intended to generate, with varying levels of autonomy, content such as complex text, images, audio, or video”. ^

- Title IV deals with transparency requirements for certain AI systems: AI systems intended to interact with natural persons, emotion recognition systems or a biometric categorization system as well as systems used to generate deep fakes need to disclose the use of AI to their users.

^ - On this point see also the this recommendation contained in a recent policy paper published by the AI Now Institute in which more than 50 leading AI experts and academics argue for meaningful safeguards to be applied to the development and deployment of GPAI/foundation models: “Regulation should avoid narrow methods of evaluation and scrutiny for GPAI that could result in a superficial checkbox exercise.”^

- For background on this see our recent analysis of the interaction between the EU copyright rules and generative ML training and COMMUNIA’s recent policy paper on the same issue which argues that “The EU should enact a robust general transparency requirement for developers of generative AI models. Creators need to be able to understand whether their works are being used as training data and how, so that they can make an informed choice about whether to reserve the right for TDM or not.”^

- See Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers.^